A longtime contributor to the growing body of research into the phenomenon of women’s invisible labor, Eskenazi School Associate Professor of Photography Elizabeth M. Claffey will further that inquiry with an upcoming project funded through a Fulbright Scholar Award. Notified March 6 of the award, Claffey will undertake creative research into women’s work and craft in Murcia, Spain during the fall of 2023. Claffey, who previously received a Fulbright Fellowship in 2012 to pursue research in Eastern Europe, will create a body of photographs exploring how contemporary Spanish women have coöpted a historically derogatory term for women’s work — tejemaneje – for their empowerment.

The term “invisible labor” “describe[s] forms of women’s unpaid labor like housework and volunteer work that, while integral to the functioning of society, [are] not regarded as work and [are] culturally and economically devalued” (Harvard Business Review).Coined in the 1980s by sociologist Arlene Kaplan Daniels, the term has become increasingly relevant in the wake of the domestic upheavals prompted by the global pandemic.

Even before COVID, a 2020 UN Reportshowed, women across the world were spending three times as many hours as men in unpaid care and domestic work. When the pandemic placed even more demands on those holding down the fort, something had to give. In COVID’s first two years, more than a million women left the American workforce, according to the National Women’s Law Center. Among many other revelations, the global health crisis definitively exposed the heavily gendered division of labor and the vulnerability inherent in that inequity.

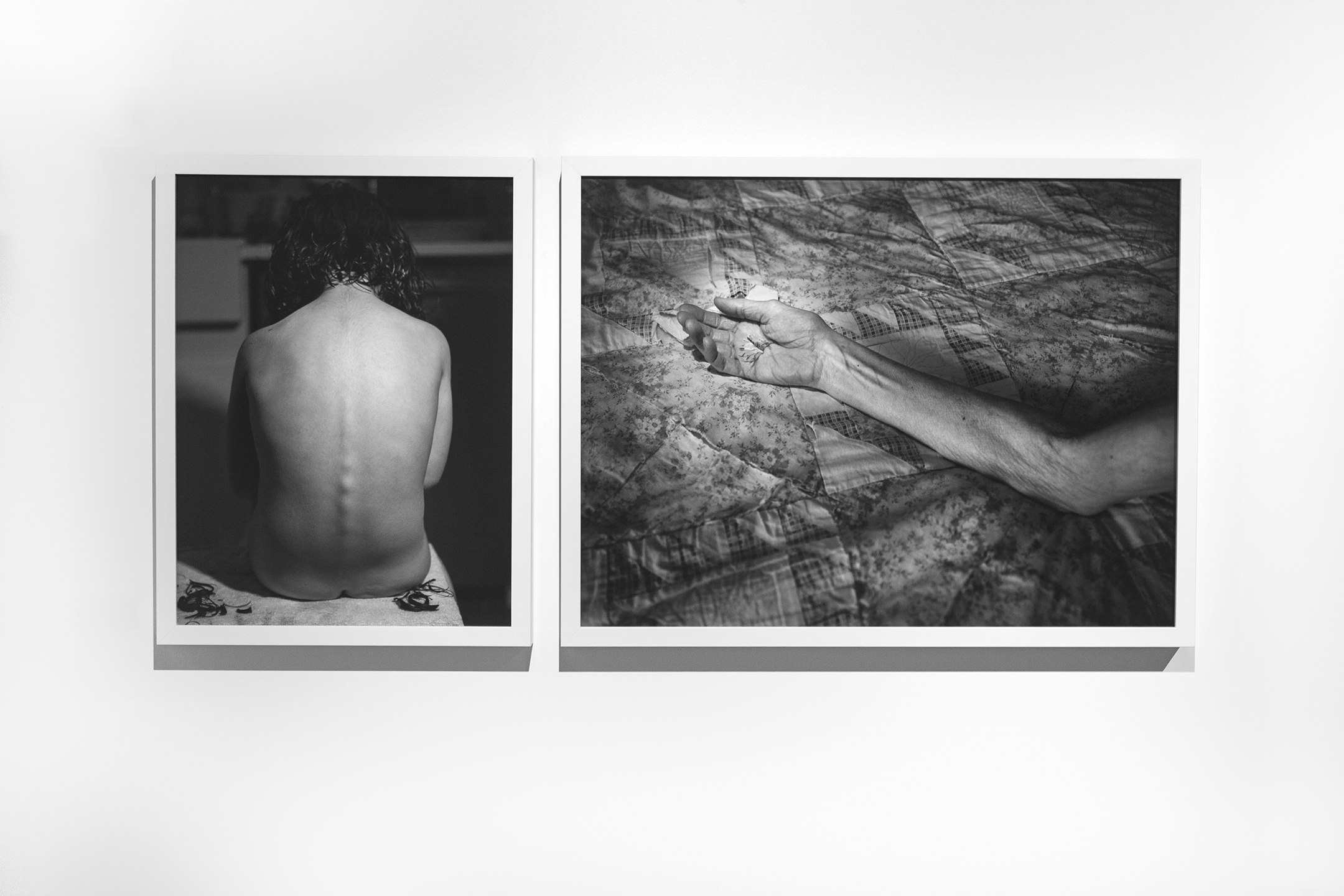

Claffey’s Fulbright-funded project, "Visualizing Labor: Memory, Craft, and Agency," will center several collective craft-making traditions passed down through generations of Spanish women. In her photographs, Claffey intends to focus on the processes — rather than the finished products — associated with encaje de bolillo (lacemaking), esparto (grass weaving), and bordado (embroidery).

Through photograms of the materials often discarded in the process of craft-making — thread, wax paper, and needles, for example — Claffey will seek to enshrine the evidence of craft-making processes that, she writes, “often happen [] in private and [are] deemed lacking in economic value by societal standards.” She aims to pay special attention to the mistakes that reveal a learning process and intergenerational conversations.

Historically relegated to the lower rungs of the hierarchy of the arts for their association with women’s work, collectively practiced crafts such as weaving and textiles possess an undersung value as a repository of “the stories that construct familial and cultural identity,” such as “the record of a death or birth and stories of cultural value such as war or famine,” Claffey writes. She contends that the transmission of these stories and craft-making skills is a “way to articulate social culture and citizenship.” As such, these traditions represent yet another form of women’s invisible labor, an “inadequately studied form of caregiving that is required in tandem with the physical labor of childbearing and community care work.”

Claffey will engage with a Spanish word that serves as a synonym for “women’s work” and also for “gossip,” among an array of connotations, to explore how the concept of tejemaneje has served historically to maintain the lowly status of women-led craft traditions. In her research and artwork, Claffey intends to explore how the term is being “subverted for personal agency” by Spanish women.

Claffey learned the term that became a “driving force” in her proposed research from Verónica Perales Blanco, an artist and professor at the University of Murcia with whom she became connected. “We bonded immediately over our shared thematic interests,” said Claffey. “[Blanco] is currently organizing research panels and discussions with women across Spain focused on unpacking and reclaiming the term, the meaning of which can vary according to region.”

Claffey’s research and creative activity have long engaged with comparative instances of women’s relationships with rituals of caregiving and labor. In addition to her work in Eastern Europe, she also received funding to conduct research in Aarhus, Denmark at the Women’s Museum.

During her Fulbright year at the University of Murcia, Claffey will also teach a seminar on advanced photography and visual storytelling in the university’s fine arts department, engage in studio visits with current students, and provide a lecture on her research to accompany an exhibition of work at the university during the fall semester.

The Fulbright Program, according to its website, was established to increase mutual understanding and support friendly and peaceful relations between the people of the United States and the people of other countries. It is the U.S. government’s flagship program of international educational and cultural exchange, offering students and scholars in more than 160 countries the opportunity to study, teach, conduct research, exchange ideas, and contribute to mutual understanding. Fulbright alumni include 62 Nobel Laureates, 89 Pulitzer Prize winners, 78 MacArthur Fellows, and thousands of leaders across the private, public, and non-profit sectors. Since its inception in 1946, the program has supported over 400,000 Fulbrighters. The program is supported through funds appropriated annually by the U.S. Congress and its operations are overseen by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.